Research Findings: Gender: Effects of masculinity and femininity on health Summary Papers

Men with higher ‘femininity’ scores have healthier hearts

Men have noticeably higher rates of coronary heart disease (CHD) than women that are often explained in terms of biological and behavioural risk factors. However, few studies have looked at psychological differences relating to gender as a potential risk factor.

Using data from the oldest cohort, born in the 1930s, from the Twenty-07 Study, this project aimed to examine the relationship between measures of ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’ against death from CHD over 17 years from 1988 to 2005.

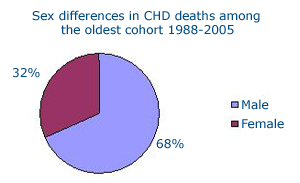

As expected CHD was the main cause of death and was higher among men than women, as Figure 1 below shows, 68% of all CHD deaths were men, and 32% women.

Figure 1: Sex differences in CHD deaths

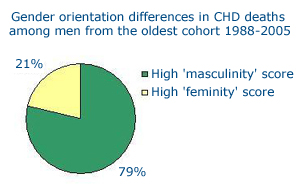

Deaths from CHD were found to be significantly lower among men with high ‘femininity’ scores (as Figure 2 below shows), in other words, had more feminine traits such as being affectionate, understanding, sympathetic, compassionate and sensitive to the needs of others. This relationship held true even after adjusting for several factors including binge drinking, smoking, body mass index, income and blood pressure).

Figure 2: Gender orientation differences in CHD deaths

‘Femininity’ score was unrelated to risk of CHD in women. There was no relationship between ‘masculinity’ score (leadership ability, aggression, dominance, risk-taking, independence, strong personality and willingness to take a stand) and deaths from CHD in men or women however. These results suggest that social concepts of gender influence the risk of ill health from CHD.

Hunt, K., H. Lewars, et al. (2007). "Decreased risk of death from coronary heart disease amongst men with higher 'femininity' scores: a general population cohort study." International Journal of Epidemiology 36 (3): 612-620.

open access

Sex, gender orientation, gender role attitudes and mental health in three generations

The increase in young male suicide rates in many countries has heightened interest in whether suicidal thoughts and behaviours are related to ‘masculinity’. This project investigated whether gender role orientation (‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ scores as measured by the Bem Sex Role Inventory) and gender role attitudes were related to serious suicidal thoughts (thoughts of overdose or deliberate self-harm) through early adulthood to late middle age.

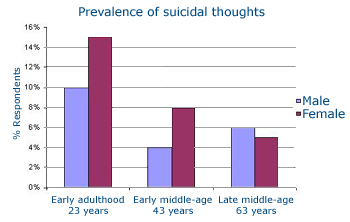

As the Figure 1 shows, both men and women had higher levels of suicidal thoughts in early adulthood than in older ages which points to the importance in understanding mental health problems at an earlier age. In early adulthood gender but not ‘masculinity’ score, was significantly related to suicidal thoughts, with women at higher risk.

Figure 1

In early middle age higher masculinity scores, but not ‘femininity’ scores, among both men and women were associated with fewer suicidal thoughts. By contrast, having more ‘traditional’ views on male and female gender roles was associated with more suicidal thoughts. The results suggest that more attention should be paid top gender roles and attitudes in older adults in research of suicidal thoughts.

Hunt, K., H. Sweeting, et al. (2006). "Sex, gender role orientation, gender role attitudes and suicidal thoughts in three generations. A general population study." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41: 641-647.

Perceptions of ‘being a man’ and gender roles among older men

Over the past two decades, theories that view men as a uniform group, united through the "biological fact of maleness", have moved towards a broader focus on multiple “masculinities” that emphasises differences and diversity among men. Despite the recent interest in multiple "masculinities", previous research has either ignored older men or treated them as without gender.

In order to fill this gap in the research, we interviewed men born in the early 1930s sampled from the oldest cohort of the Twenty-07 Study. Disruptions to individual life histories (due to the illness or death of a spouse or loss of their job through redundancy) forced men to reassess previously taken-for-granted attitudes to gender roles. Social class paths were important in shaping men's attitudes to paid work and gender roles; for example, we found that the more socially and financially successful men were, the more democratic they were about the gendered division of housework. More privileged men were found to construct ‘masculinity’ differently from more disadvantaged men. Having a greater understanding of the variety of ways in which older men perceive ‘masculinity’ and gender roles in their daily lives will be useful for developing more effective health promotion strategies.

Emslie, C., K. Hunt, et al. (2004). "Masculinities in older men: A qualitative study in the west of Scotland." The Journal of Men's Studies 12(3): 207-226.

‘Masculine’, ‘feminine’ identities and class differences in smoking among men and women

Developing effective health promotion campaigns to reduce high smoking rates in Scotland, particularly in the West, are a key public health priority. Previous research tells us that patterns of smoking by class, gender and gender role identities may differ markedly across generations.

Examining all three cohorts of the Twenty-07 Study, we found class trends in smoking were more apparent in women than men in the older two cohorts (with greater rates of smoking reported among manual social classes), and there was little evidence of class trends in either sex in the youngest participants. There was little relationship between the measures of ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ and current smoking among men. By contrast, stronger ‘feminine’ identities almost doubled the chances of being a smoker among women in the 1950s cohort. In this same cohort of women, there was a weaker relationship between smoking and higher ‘masculinity’. We suggest that smoking education programmes make new generations of potential smokers aware of the variety of ways in which the tobacco industry manipulates gender role perceptions and idealises cultural images to exploit new markets for their products.

Hunt, K., M. K. Hannah, et al. (2004). "Contextualising smoking: masculinity, femininity and class differences in smoking in men and women from three generations in the west of Scotland." Health Education Research: Theory and Practice 19(3): 239-249.

Gender and health

Gender is one of the key social variables being examined in the Twenty-07 Study. Analysis of second wave (1990/1) data has suggested that the picture of greater female poor health for most health outcomes is an oversimplification. Sex differences in health are not as clear or consistent as is often assumed. Excess female poor health is only consistently found across the life span for psychological stress and is far less apparent, or reversed, for a number of physical symptoms and conditions.

It has been suggested that sex differences in health may be a consequence of differences in risks gained by the social roles, lifestyles and health behaviours that men and women engage in, such that women’s poorer health is rooted in their life circumstances and experiences. There is limited understanding of the mechanisms linking gender and health. While it may be reasonable to expect most women to adopt socially defined female gender roles and most men to adopt socially defined male gender roles, there is no reason to expect all men or all women to do so. We wanted to find out the extent to which gender-role expectations cross-cut sex.

In the 1950s cohort from the Twenty-07 Study, we explored in broad terms whether gender roles and gender role orientation have a significant effect upon health.

We found that the effect of gender role orientation is at least as important as the effect of being male/female on several aspects of health. In both men and women a high ‘masculinity’ score was associated with fewer symptoms, even after controlling for sex and femininity score. Conversely, a high ‘femininity’ score was associated with more symptoms (sex and masculinity score controlled for). These findings were found for other, but not all, health measures.

Traditionally found differences in health between the sexes may mask a general association between ‘femininity’ and poor health and ‘masculinity’ with relatively good health in both men and women. Further research will help establish whether a particular gender role selects an individual into particular life circumstances and social status (such as marriage, parenthood, unemployment) or whether it is particular circumstances and social status that select an individual’s gender role orientation.

Annandale, E. and K. Hunt (1990). "Masculinity, femininity and sex: an exploration of their relative contribution to explaining gender differences in health." Sociology of Health and Illness 12(1): 24-46.