Research Findings: Where people live: Impact of where you live on what you eat Summary papers

Changes in diet and food access from 1992-2002

The influence of the neighbourhood environment

Availability and price of healthy foods likely to influence dietary behaviours and health-related outcomes varied between the two localities studied in more detail as part of the Twenty-07 Study. Dietary habits and body shape and size were found to be independently related to neighbourhood of residence. In other words, for diet, places are as important as people.

A shopping basket survey in the early 1990s demonstrated that in the more deprived locality, ‘healthy’ foods cost more and were less available, and fruit and vegetables were of poorer quality than the more affluent Study areas.

Price influences consumer retail choices especially for lower income groups and food sold in supermarkets is cheaper than in local corner shops. Although overall most grocery shopping is done in supermarkets, the local corner shop is still the main supplier of basic food items (e.g. bread, milk, fruit and vegetables) for more disadvantaged socioeconomic groups and those living in more deprived neighbourhoods. This is mainly due to their lower rates of car ownership, reliance on public transport and lesser spending power.

In the late 1980s, more food retail outlets existed in the more affluent locality compared to the more deprived area. This difference has narrowed over time, partly due to a fall in provision in the more affluent area, although the deprived locality is still not as well-served by the commercial sector. In contrast, an expansion in voluntary sector activity on the food front (e.g. Fruit Barras, Get Cooking Classes) is much greater in the deprived locality.

Changes in dietary behaviour

Data from the Twenty-07 Study show that overall levels of fruit consumption have increased over a ten year period (1992-2002). While the levels of fruit consumption are higher among those living in the more affluent locality, the rate of improvement is greater among adults living in the deprived locality particularly the cohort born in the 1950s). This pattern of change is confirmed by other population surveys.

The findings of a PhD study by Ebrahimi-Mameghani (2004), which compared Twenty-07 respondents’ dietary intake with the recommendations of the Scottish Diet Action Plan (SDAP), showed that respondents had made modest but significant changes in eating behaviours over the study period and these were in the direction of the recommended targets. Around half the respondents met the SDAP targets for breakfast cereals and oily fish while the targets for bread, fruit and vegetables were not met by the majority of respondents.

Overall, respondents regard their diet as being less healthy than they did in the early 1990s. This may reflect increased awareness over the time period of what constitutes a healthy diet and a revised assessment of their status in this regard.

Conclusion

Actions to improve the Scottish diet and change eating/shopping patterns need to address the food retailing and food production characteristics of neighbourhood environments in order to improve access to affordable healthy foods in poorer areas. A faster rate of improvement in fruit consumption among more disadvantaged social class groups may reflect the growth of local activity ‘on the ground’ (e.g. community food initiatives to improve access to healthier foods) by agencies in deprived areas although a special study is required to confirm this.

Ellaway, A. (2005). Changes in diet and food access, 1992-2002: A review of existing findings within West of Scotland Twenty-07 Study. Confidential Report to Healthy Scotland’s Review of the Scottish Diet Action Targets. Glasgow, MRC SPHSU.

open access

Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M. (2004). A longitudinal study of eating behaviour and weight change in West of Scotland adults: association with socio-demographic and lifestyle factors. Department of Human Nutrition. Glasgow, University of Glasgow.

Does where you live increase your risk of obesity?

The rapid rise in obesity among Scots shows little sign of slowing down. It is now estimated that 64% of men and 57% of women in Scotland are either overweight or obese, contributing to a wide range of health conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke and certain cancers. Identifying those factors that influence people’s weight will help develop better understanding and more effective public health strategies to tackle the obesity problem and support people in leading healthier lives. An earlier study in the West of Scotland (Ecob, 1996) found that factors such as abdominal fat, blood pressure and respiratory symptoms are independently linked to the postcode area in which a person lives.

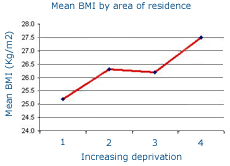

This project took further measures of height, weight, body mass index, waist circumference and waist-hip ratio from the second wave of the Twenty-07 Study for the two adult cohorts living in four socially contrasting neighbourhoods in the West of Scotland to examine whether the place where a person lives affects their body size and shape. We found that the area where a person lives can determine their body size (as in Figure 1: BMI, height) and shape (as in Figure 2: waist circumference, waist-hip ratio).

Figure 1: Mean body size by area of residence

Figure 2: Mean body shape by area of residence

Those living in the most deprived communities were significantly shorter, had bigger waistlines and were heavier than those living in affluent areas. Therefore, to help tackle the rise in obesity, public health policy should focus, not only on the people themselves but also on the places where people live, and in particular poorer communities.

Ellaway, A., A. S. Anderson, et al. (1997). "Does area of residence affect body size and shape?" International Journal of Obesity 21: 304-308.

Ecob, R. (1996). A multilevel modelling approach to examining the effects of area of residence on health and functioning. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 159 (1): 61-75

Does where you live predict healthy habits?

In a study of the two older cohorts when they were aged 40 and 60 years and living in four socially contrasting neighbourhoods in Glasgow (West End, Garscadden, Mosspark and Pollock) we found that patterns of diet, smoking and physical exercise were worse in more disadvantaged neighbourhoods (even after taking into account differences between the neighbourhoods in age, sex, and household income) than in more affluent places. Policies aiming to improve the health of the population need to take into account the characteristics of local neighbourhoods (for example, the availability and price of healthy foods, local culture and role models in regard to smoking, and ease of access to sports facilities) as well as the people living within them.

Ellaway, A. and S. Macintyre (1996). "Does where you live predict health-related behaviours? A case study in Glasgow." Health Bulletin 54(6): 443-446.

pubmed

Barriers to healthier food options in poorer areas

Eating plenty of fruit and vegetables and oily fish as part of a healthy balanced diet is known to offer some protection against heart disease, diabetes and other life-threatening conditions. It is also known that those living in poorer areas, especially in Scotland, eat the least fruit and vegetables and oily fish.

This study explored whether differences in the cost and availability of common food items exist, and focused particularly on the extent to which healthier options may differ in price and availability between two socioeconomic contrasting neighbourhoods with the Twenty-07 Study. We compared the price and availability of a chosen “shopping basket” of ‘healthy’ foods which people are encouraged to eat more of and a basket of ‘less healthy’ foods which people are encouraged to eat less of between shops in the North West and South West Glasgow localities. To carry out a fair comparison of products between shops we made sure the items were the same size, weight, quality, quantity and brand wherever possible.

We found that 60% of the items in the ‘healthy’ basket were 5% more expensive in the poorer South West than in the better off North West area. Fewer shops in the South West stocked ‘healthy’ items. Moreover, there were marked differences in the quality of fruit and vegetables between the two localities, with the South West having poorer quality than the North West. Fewer shop in the South West sold fresh fish, considered a ‘healthy’ option (or fish of any kind). The price of either basket was more expensive in the South West than the North West. Overall, there was a greater disadvantage in the South West in terms of price and availability of ‘healthy’ foods. We suggest that health promotion strategies need to take into account issues of availability and price of foodstuffs in disadvantaged areas as they may act as a barrier to healthier options for people living in such areas.

Sooman, A., S. Macintyre, et al. (1993). "Scotland's Health-a more difficult challenge for some? The price and availability of healthy foods in socially contrasting localities in the West of Scotland." Health Bulletin 51(5): 276-284.

pubmed